Our mobile devices do so many things for us, making it easy to communicate with people in all manners while giving us access to all sorts of information wherever we are. But in times of anxiety and panic, it is difficult to quickly use them. Will you be too shaky to type in your PIN or lock pattern? Will you have enough time to find your trusted contacts and send them a message? On top of that, our mobile devices carry massive amounts of private information in them: banking details, pictures, all of our messages and call logs.

Our mobile devices do so many things for us, making it easy to communicate with people in all manners while giving us access to all sorts of information wherever we are. But in times of anxiety and panic, it is difficult to quickly use them. Will you be too shaky to type in your PIN or lock pattern? Will you have enough time to find your trusted contacts and send them a message? On top of that, our mobile devices carry massive amounts of private information in them: banking details, pictures, all of our messages and call logs.

The kinds of data that we worry about vary widely based on where we are. In many places in the world, the stuff you are reading or the music you are listening to can get you arrested, or the people you are communicating with is enough to send you to jail. We have been adding “panic buttons” to our apps for 5 years now, and now we want to create an ecosystem of apps to create flexible and system-wide responses when we are unfortunate enough to require pressing the personal panic button.

This work seeks to establish a new level of awareness, understanding and capability for providing specific mobile software features for users who are in a “panic” situations. We define “panic” as at risk of having their mobile device physically compromised or removed from their body, being physically detained themselves, or facing an immediate threat of violence, injury, kidnapping or death. This is not to say we are are building a global “911” system. We seek to explore how software that is explicitly designed for these situations, can provide some amount of assistance to the user, by either protecting their privacy, ensuring that sensitive data is hidden or unrecoverable, or that their support networks are notified of the panic event, and provided with the necessary information to take action.

Over the past year, we have developed user experience design patterns, an Android library, a new panic button app, and example projects to communicate how a system-wide panic should look. For a quick introduction, check out this video demonstrating a very simple panic setup of Ripple, a panic button, triggering Orweb, a private browser:

Make your app respond in times of panic

The ultimate goal of PanicKit is of course to make apps respond with actions that help protect the user. This can be as simple as locking the app when it has a passphrase, or the response can combine a number of actions into a coherent response: a messaging app locks its data and disguises itself as a game while sending out the panic message that includes the user’s location. There is a lot of complexity in all this, especially with many apps involved, so it is essential to always simplify the experience as much as possible. Thinking about panic situations is stressful, setting up the panic response should not add to that stress. Towards that end, it is better to sacrifice some flexibility if that means solid gains in simplicity.

The first key design pattern is the default, non-destructive response. If all apps that support PanicKit include sensible defaults, then pressing the panic button can have a useful response without the user having to setup anything at all. In order to achieve this, we divide possible responses into two categories: non-destructive vs destructive. An app that has a PIN lock can be locked without destroying anything, the user just needs to unlock it. A browser that wipes the cache can always just download the files again next time the user goes to that website. If an app only has a default, non-destructive response, then there is no need to have a configuration interface; it can be represented purely in the trigger app’s list of responders, where it will be marked “App hides when triggered”.

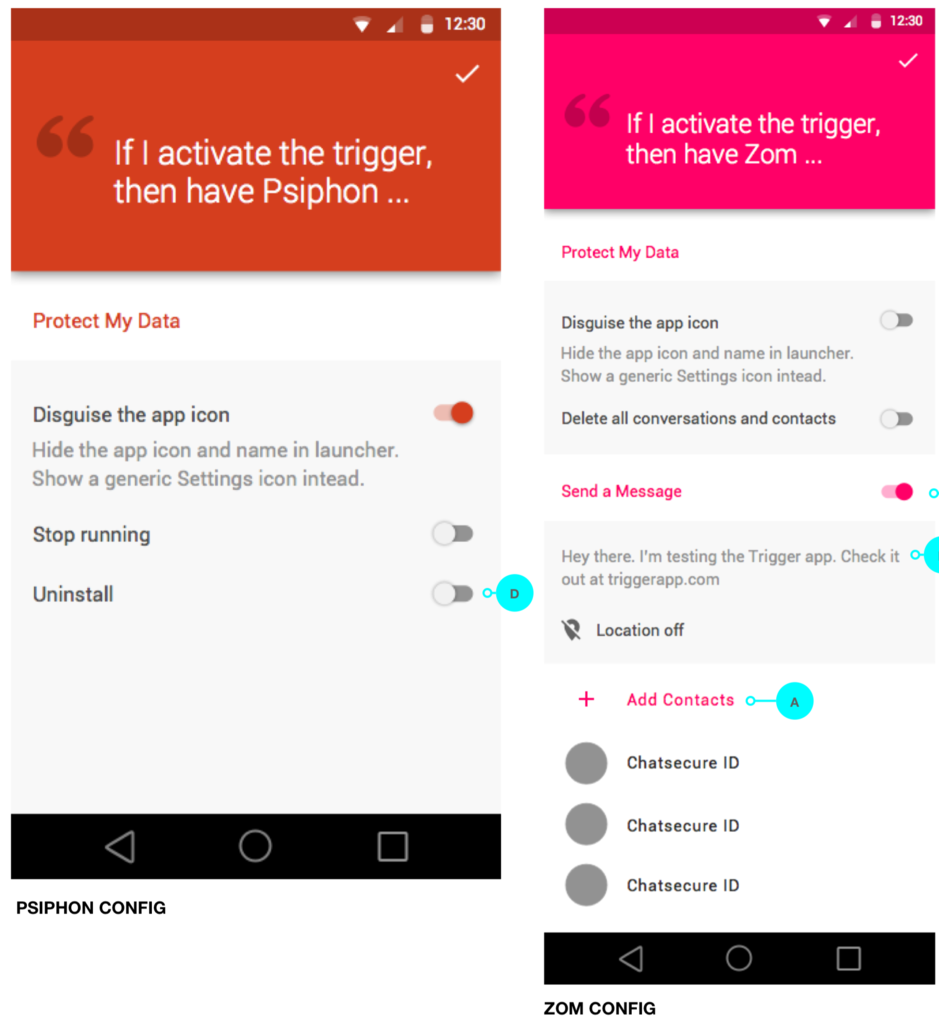

Many of the most valuable panic responses require doing something that can not be undone, so we classify these as destructive. Deleting data is exactly what is needed in a panic situation, but the user must opt-in to enable this kind of response in order to prevent data from being mistakenly deleted. Sending a message can also be a very valuable panic response. But sending a message to the wrong person can cause harm, sending it at the wrong time can destroy people’s expectations: if you cry wolf too often, then people will stop hearing it. Disguising an app can also save people a lot of trouble. But if the user does not know this is going to happen, their experience will be that the app was deleted. So these are all destructive responses and require the user to enable them via a panic setup screen.

For apps that offer configurable responses, it is essential to present those options clearly with as little clutter as possible. The panic setup should be on a devoted screen, not mixed in with other settings, and takes up the full screen. Panic is a time of stress, the panic response should strive to avoid adding any stress on top of that. When an app offers a few options for responses, then even the devoted screen can quickly get complicated: a list of possibilities, a text field for a message, and a way to manage the contacts to send to. It is important that the entire response is easily visible in one screen so that the user can quickly and easily tell how that app will respond. The entire panic setup should be on a single screen with as little scrolling as possible. Large widgets like a message text field should be placed at the bottom, and be collapsed if not active.

To get started, add the PanicKit library to your build.gradle: info.guardianproject.panic:panic:0.5, then check out the FakePanicResponder example app, as well as how it is implemented in real apps:

- SMSSecure lock as default response

- NewPipe clear search history as default response

- Zom with multiple destructive responses and a default lock response

Make your own panic button app

One key reason why we took on this project is to spur more innovation in what a “panic button” can look like. There are currently two solid panic trigger apps that use PanicKit: PanicButton and Ripple.

There are many ideas for what a panic button can look like, now it is easy to make one that will actually trigger real things. A custom panic button app only needs to send the trigger message (technically an ACTION_TRIGGER Intent), which will make apps lock, hide, delete private data, send a message, etc. Here are some ideas for panic button apps that we would love to see:

- a “dead man’s switch” that triggers if the user has not checked in within the last hour

- a “geo-fence” that triggers if the device comes too close to a known detention center

- a sensor monitor that triggers on absence of movement

- a custom Bluetooth button that looks like a belt buckle, brooch, or other innocuous object

An important part of the user experience of the panic button app is how it represents what the trigger will do. For that, we paid careful attention to the design of the list of “panic responder” apps. It should quickly and clearly show which apps are enabled. In our pattern, enabled apps should be sorted to the top of the list and disabled apps should be greyed out including the app icon. There should also be a standard switch to both allow the user to enable/disable an app as well as provide extra feedback on whether an app is enabled or not. That provides three visual channels that communicate what will respond (top of the list, in full color, and with the shape of a switch that is turned on). For a thorough overview of design patterns, see Panic Design Patterns.

Panic responders can have both non-destructive and destructive responses, and some are only appropriate for a full on panic. If you are just feeling anxious, and are worried that the situation is getting dangerous, then deleting files is not appropriate but locking and hiding is. An app could instead be an “anxious trigger” app, and be limited to only non-destructive responses. A trigger app can only send one kind of trigger message (the ACTION_TRIGGER Intent), to keep the inter-app interaction simple. So the anxious trigger app would instead not offer the “EDIT” option (implemented with an ACTION_CONNECT Intent), and that limits the responses to the default, non-destructive responses in all the apps that receive a trigger from the anxious trigger app.

To get started, add the panickit library to your build.gradle info.guardianproject.panic:panic:0.5, then check out the PanicTrigger class. You can see how it is implemented in these example apps:

- Ripple – a real panic button that is simple enough to be an example

- FakePanicButton – a fake app that is only meant to be an example

More work and open questions

There is a lot of potential for making our mobile devices help us in anxious and panicked moments. PanicKit has established that a system-wide panic response can be simple, approachable, and effective. But there is definitely much work to be done. There is an organization forming around this work, The Panic Initiative, that will build upon the work done by Amnesty International, iilab, and our PanicKit work.

There are of course still many open questions that we are very interested in, and hope to see more people working on this:

- Should this be handled on the system level?

- How the trigger app query the responder for its action without leaking private data like contacts or location?

- How can panic and anxiety be represented graphically, using colors, iconography, UI, etc.?

For more discussion and resources, check out the PanicKit wiki.