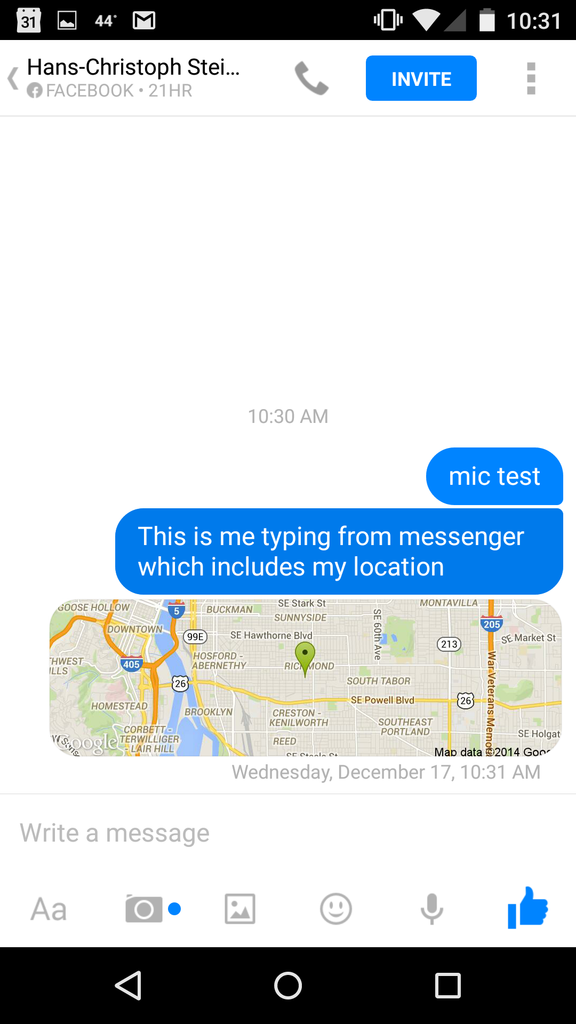

Facebook location sharing embeds the location in every single message, providing a detailed log to the recipient, Facebook, and anyone Facebook shares that data with

One handy feature that many smartphones give us is the ability to easily share our exact position with other people. You can see this feature in a lot of apps. Google Maps lets you click “Share” and send a URL via any method you have available. In Facebook Messenger, you can click a button and the people on the other side of the chat will receive a little embedded map showing the received location. Of course, the question we always ask is: how can we do this in a privacy-preserving way? And the follow up question: what kinds of information are apps leaking, storing, using, etc? Location is especially valuable and sensitive metadata, especially when there is a lot of it, because it can be used to derive so much information about a person. Most people do not want to publicly post their phone number or home address on the internet, yet are unwittingly giving away far more detailed information by using the various location-based services that are available. There is a lot of specific location information that people do not want to publicize that they visit: a cancer specialist, an abortion clinic, a criminal court, a mistress’ house, or any location information to an abusive spouse. For a great illustration of the power of location metadata, you can watch an animation of German politician Malte Spitz’s life, based on his telephone metadata that his telecom had stored.

Google, Facebook, and so many others make money by collecting as much data on their users as possible, then selling access to that data to their customers. So both those companies have incentives to make sure that you will always share your location information with them as well. The question is: are they treating this information as carefully as you would? In China, the indigenous services are much more popular than most foreign alternatives. The Chinese companies are good at making products that are popular with Chinese users, and since they collaborate with the government censorship and tracking, it is easier for them to do business in China. This combination often means that Chinese companies put security and privacy at a very low priority, even though they could comply with the Chinese law while improving their security. A good example of this is the fact that none of the major map providers in China (Baidu, Amap, or QQ) provide even an optional HTTPS interface. They only have unencrypted communications, which allows lots of people easy access to snooping, including anyone who is on the same wifi network as you are.

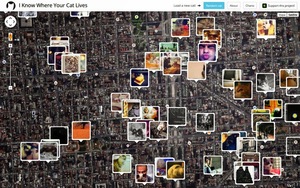

The tools for tracking people via location data are getting better, cheaper, and more available. One funny example is I Know Where Your Cat Lives, which shows the locations of cat pictures found on the public internet via the geo location included in the EXIF image data.

Location and Panic

One use that we are particularly interested in is sending location to trusted contacts when a panic button is pressed. When thinking about panic button features, privacy must be a central concern. When someone triggers their panic button, it is clearly a sensitive situation. That means that leaking more location information could exacerabate the situation. Since sending location is a useful and popular feature, it is important to consider the whole picture of where that location information might go. To start with, the panic message needs to be sent using a method that will reliably reach its intended destination. Unfortunately, that often means using insecure communications like SMS, or an app that is fully tapped by the same government that is detaining the user, like WeChat. Part of this T2 Panic research and development effort is focused on how to make a complete, secure panic solution. So we will also focus on making ChatSecure and other secure communications an available channel for sending panic messages.

The next step is to break down the entire path of where that location information might be intercepted. The first place is on the sending device itself. The panic message will stored with the sent messages with most communications apps, and that can recovered by whoever is detaining the user. Even if the device is encrypted, it is very likely the user can be compelled to unlock the device. So the panic message should be designed with that in mind.

The next step is to break down the entire path of where that location information might be intercepted. The first place is on the sending device itself. The panic message will stored with the sent messages with most communications apps, and that can recovered by whoever is detaining the user. Even if the device is encrypted, it is very likely the user can be compelled to unlock the device. So the panic message should be designed with that in mind.

So if we consider a fully anonymous method of communication, like ChatSecure’s “Secret Identity”, then protecting the location information becomes important even if all of the messages and their recipients are recovered from the sending device. The full “Secret Identity” procedure of creating an account per person you want to chat with, and only using that single account to communicate with that other person. It has been outlined by many people, including Laura Poitras when describing how she communicates with Edward Snowden. In this case, even if someone recovers the recipient address, all they will have is an anonymously created account with no other links to other accounts. Then location URL then becomes a way to deanonymize the recipient. First, if the URL takes the recipient to an unencrypted connection, then that it is easy to track. Even with an encrypted connection, if the server providing the map service is providing information to the government, then the encrypted connection will not help. Making this connection over Tor will also help since the map service will not be able to see the IP address of the device where the user clicked on this URL. Now consider a location URL using Google Maps, or any similar service where users frequently login. If the original panic message was sent using such a URL, and the recipient was a regular user of a service that used logins, then that login information would deanonymize the recipient if they viewed the location URL in a browser where they were also logged in with their normal Google account.

User Stories

This can perhaps be better illustrated using some quick user stories:

- A journalist and a source set up Secret Identities in ChatSecure devoted to each other when they met up in person. Each have panic buttons set up to contact the other in case of emergency. The journalist uses

https://openstreetmap.orgto generate a shortlink that points to the chosen meeting location, then sends it to the source using the Secret Identity,http://osm.org/go/0ju_SMlBn. The source clicks the link, and chooses to open the link in Firefox. Therefore, the website is shown using an unencrypted, direct connection, which is easily observed. Even though the recipient has HTTPS Everywhere set up in his browser to force HTTPS for openstreetmap.org, the osm.org shortlink does not currently have working HTTPS so it is an HTTP link. This shortlink is now a unique ID that links the journalist and source’s real IP address. If the source was using a cellular internet connection, then this will also link the IP address to the devices IMEI unique ID. The IMEI is then quite easy to link to a real identity information. - A circle of activists all set each other up with a panic button app on burner Android phones. They only use these burner phones to communicate with each other. They prepare in advance to discard all the phones in case someone triggers the panic. One activitist gets detained by the secret police and triggers the panic. The secret police get the panic message and all the other phone numbers from the detainee’s phone, but the activists are no longer using those phones so they cannot be tracked by them. The activists manually copy the Google Maps shortlink

https://goo.gl/maps/Cji0Vto their computer to find out where the detainee is. They type the map link into Internet Explorer, making sure to type HTTPS, and then again confirm that the webpage is still using an HTTPS link. What they did not see is that the shortlink first redirected to a HTTP linkhttp://maps.google.com/?q=28.118860,98.008069&hl=en&gl=us, which leaked the location in plain text. Since this URL describes a very specific point, the secret police use this as a data point to search for the IP address of all devices that have accessed that URL. Those IP addresses divulge the locations of all the activists who viewed the map URL, and provide the secret police a method for tracking them all.

I did not cover other more common use cases here because there are so many leaks that the protections presented are moot. All is not lost, there is still a lot that you can do to improve things. First off, we recommend using map apps that can work fully offline. For Android, Osmand is the best one out there, it uses OpenStreetMap data which can be freely downloaded. It is also important to encourage developers to improve the privacy of their apps. Since we are software developers, we file bug reports and make pull requests to nag location-related projects to improve their security. Here are some recent examples of what we have contributed:

OpenStreetMap

- Issue #799: Implement

geo:URLs for sharing - Issue #870: share makes HTTP url even when connecting via HTTPS

- Issue #862: support osm.org in HTTPS certificate

Osmand

- Pull #1033: modernize location sharing

- Pull #1043: add support for a proxy and use more HTTPS

- Pull #1045: update URL parsing

We will be following up with further posts on this topic with more detail, including research into what is possible to derive from location data, technical details of issues, and possible solutions and work that can be done to improve things.