There are many ideas of core architectures for providing digital services, each with their own advantages and disadvantages. I break it down along the lines of central servers, federated servers, and peer-to-peer, serverless systems.

Most big internet companies operate in effect as a central server (even though they are implemented differently). There is only facebook.com, there are no other services that can inter-operate with facebook.com. Have a single, central repo makes problems of finding the service and finding people within the service a lot easier. Once you are in Facebook, you just need to know the name of the person you want to contact and you are connected. The Facebook apps just need to talk to facebook.com, so the user does not need to know which service they are using in order to configure the app.

Email is a great example of a federated system. Each email provider acts like a central server, but then each of those central servers can easily talk to each other and exchange data. So fastmail.fm and gmail.com are both centralized services, but users do not need to know any extra information in order to exchange emails between the two services, or any other of the millions of email servers out there. A federated system provides a lot of the benefits of a centralized server with more flexibility. The downside is that federated services generally require more configuration to use them (though webmail makes that much less of an issue).

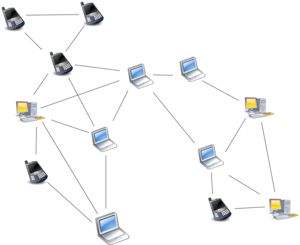

Peer-to-peer systems can provide unique benefits of bandwidth efficiency as well as working around blockages in the internet. Sharing large files with thousands of people is quite expensive when using a central server, but with bittorrent, anyone can share large files to many many people using only a basic broadband connection.

Over the past year and a half of our Bazaar project, we have been thinking a lot about how to distribute apps to people who face a number of challenges. Each of these systems offers distinct advantages and disadvantages, so it is quite difficult to choose only one. Instead, we thought why not try to make a system that combines all three? Android’s APK app package format is a good format to work in this model because they are self-contained and containing a form of embedded identity in the app signature. So if you already have an Android app installed, then Android will enforce that only APKs signed by the same key as the installed app can be installed over it.

That means in theory, it does not matter where the APK came from as long as it has a valid signature. There are some details where it does matter, mostly related to exploits like “Master Key” that can inject code into an existing APK. The FDroid app repository signature has a similar property: once you trust the repository signing key, it does not matter how you got the repository files as long as the signature validates. This is a model proven by GNU/Linux distros like Debian. The repository metadata also provides a way to validate APKs have not been modified since they were added to the signed repository. Since both of these do not rely on the method of transport to prove their authenticity, this combination provides a great testbed for this idea of combining a central service, with decentralized servers and peer-to-peer distribution.

This work was all incorporated in the FDroid app store for Android. The central f-droid.org app repository means that FDroid can deliver well over one thousand apps without any configuration on the part of the user. The “fdroidserver” developer tools means that anyone can set up their own repository of apps, and users can easily add that repository to FDroid. It is not quite zero configuration, but the process is not too difficult, and there is more we are planning to do to smooth out that process even more. This also provides a channel for users to get apps via “collateral freedom” techniques like using Amazon S3, Akamai, etc. to distribute files where many such services are filtered or blocked. Lastly, we made it possible to have the FDroid app itself act as an app repository, and other devices can connect to that repository using local WiFi, mesh, Bluetooth, and removable media.

This stuff is all implemented and included in the FDroid app and fdroidserver developer tools. The big remaining challenge is combining them all into a usable experience for people who do not know the technical details. This has been tested, discussed, sketched out, and there is a prototype implementation in the works. So I can end with a quick overview of some positive and negative observations about the various peer-to-peer connections that we experimented with:

- + Bluetooth is ubiquitous

- – very slow data rate

- – pairing is difficult

- + WiFi is very widespread

- + local connections are very fast

- – access points and proxies can block host-to-host connections

- – running access points on a device is not common nor easy

- + NFC makes Bluetooth very easy to use

- – NFC is not commonly used or available

- – NFC is far to slow and fiddly to be used as the data transmission medium

- + SD cards can move lots of data securely

- – not all devices have removable SD cards

- – swapping SD cards can be a fiddly process

- – swapping SD cards can not be automatic

- + USB thumb drives can move lots of data securely

- + they can be easily swapped between devices

- – swapping SD cards can not be automatic

- – not all devices support USB-OTG i.e. attached devices

- – USB-OTG is not widely used