For the past two years, we have been thinking about how to make it easier for anyone to achieve private communications. One particular focus has been on the “security tokens” that are required to make private communications systems work. This research area is called internally Portable Shared Security Tokens aka PSST. All of the privacy tools that we are working on require “keys” and “signatures”, to use the language of cryptography, and these are the core of what “security tokens” are. One thing we learned a lot about is how to portray and discuss tools for private or anonymous communications to people who just want to communicate and are not interested in technical discussion. This is becoming a central issue among a lot of people working to make usable privacy tools.

For the past two years, we have been thinking about how to make it easier for anyone to achieve private communications. One particular focus has been on the “security tokens” that are required to make private communications systems work. This research area is called internally Portable Shared Security Tokens aka PSST. All of the privacy tools that we are working on require “keys” and “signatures”, to use the language of cryptography, and these are the core of what “security tokens” are. One thing we learned a lot about is how to portray and discuss tools for private or anonymous communications to people who just want to communicate and are not interested in technical discussion. This is becoming a central issue among a lot of people working to make usable privacy tools.

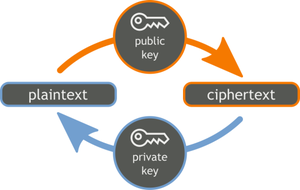

The widely established way of talking about privacy tools comes from the lingo of the underlying methods: cryptography, networking, etc. We talk about public and private keys, signing, validation, verification, key exchange, certificates, and fingerprints. In order for cryptography to work, keys need to be marked whether they are verified or not.  Few computers users understand what these terms are referring to, even highly technical people who regularly use encryption do not know the meaning of all these things, nor should they. This is a low level detail that is not important to how the vast majority of users understand privacy in computers. Keys and verification are far too abstract to be generally understandable, and what other kind of key has a fingerprint? Even more so, few people can tell you the difference between validation and verification when it comes to keys, signatures and certificates. The software should not be exposing all this, but instead should be minimizing the complexity as much as possible, and providing as simple a user experience as possible.

Few computers users understand what these terms are referring to, even highly technical people who regularly use encryption do not know the meaning of all these things, nor should they. This is a low level detail that is not important to how the vast majority of users understand privacy in computers. Keys and verification are far too abstract to be generally understandable, and what other kind of key has a fingerprint? Even more so, few people can tell you the difference between validation and verification when it comes to keys, signatures and certificates. The software should not be exposing all this, but instead should be minimizing the complexity as much as possible, and providing as simple a user experience as possible.

Defining the Concepts that Define the Experience

A key part of defining that simple user experience is defining the core concepts that the software is organized around. In our discussions, we mostly talked about the ideas of identity and trust, while some discussion of verifying identity seemed unavoidable. Talking about identity and trust is a lot more relevant in day-to-day life, i.e. knowing that the message came from the person you think it did, and trusting that it was private. It is most direct to talk about establishing a trusted connection to another person, but that’s not something that crypto can ever promise because there is still the analog gap between the person and the device. These core ideas must represent what is technically possible, so we searched for widely understood concepts that map well to the technical limitations: “a private conversation”, “a trusted app”, “verifiable video”.

Diving in deeper, we concluded that the balance point between technical accuracy and widely understandable lingo was to talk about trusting the device, not the person. The technology can provide trusted connections between devices, and it is pretty close to how people experience digital communications. There is the laptop, the mobile phone, the net cafe, the friend’s computer, computer at work, etc. etc. When I look at my phone to see a message from a friend, it is easy to picture that friend typing that message out on that device, though it does take some conscious effort. The hard part here is that as we communicate more and more with our devices, there is less and less separation in our minds about whether we were talking in person, via voice, or by sending text. This is a point to focus on when thinking about designing the experience of private, secure communications software.Let the Software Handle It!

There is a forming consensus in the world of usable security to focus on figuring out how to automate as much as possible then figure out how best tailor the experience of the essential parts that cannot be automated. The hard part will remain explaining the limitations of a given privacy tool.

At Guardian Project, we work a lot on incremental progress, so many of our projects are focused on specific, narrow improvements. With ChatSecure and Keysync , we were able to automate one small part of the whole process, cryptography identity portability, which provides the foundation to provide private communications and verifiable media. Allowing users to sync their trust profiles between desktop and mobile makes it much more likely that users will have fully verified OTR conversations when chatting on their devices and laptops.

With Gnu Privacy Guard for Android (GPGA), we have made it easy to import keys via QRCode as well as openpgp4fpr: URLs (a standard defined in conjuction with the Monkeysphere project. We are also working on a common method of using NFC for OpenPGP key signing in conjuction with OpenPGP Keychain. Even little things like optimizing support for standard file extensions can go a long way to make things easier, so GPGA automatically sets itself up to receive files with the standard OpenPGP MIME types (application/pgp-keys, application/pgp-encrypted, application/pgp-signature) as well as the corresponding file extensions (.pkr, .skr, .key, .sig, .asc, etc.). That makes it so a user can just click on one of these files, and GPGA will walk them through the whole process, doing as much as possible automatically.

Another interesting idea that is a big step in this direction is “secure introductions”. The idea is to automatically share trusted identity information when securely communicating with multiple people. For example, whenever you send a signed, encrypted email to multiple people, the email program should include the key fingerprints of each recipient in that email. Then the email program of the people receiving that email should automatically mark those keys as verified if the sender’s key is trusted and the signature is valid. There is not a meaningful amount of detail leaked in this interaction, since the existence of all the people’s keys and email address is already present in a secure email. The tricky part is figuring out how to make it harder for someone to use this maliciously to spread false identity information while keeping things as automatic as possible. This is very much a long term research idea: there are no widespread implementations of it.